Vietnamese peace worker, author and Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh explains how, with a mindful existence, you can see in a piece of paper the tree, and the sunshine the tree drank in, and the drops of rain that watered it. I try to do the same when drinking tea; to see the person who picked the tea, or rolled the tea, or pan-fried the tea, and the sunshine that bathed it, and the soil that nurtured it – all in one cup.

This same mindfulness can show us the history of tea. It is a history of great beauty and cultural significance. It is also a history of colonization, trickery, slavery, and white supremacy. Therefore, it is important to be aware of the history of colonization as it pertains to tea so that we can address its continuing impacts and create an equitable landscape for producers, distributors, creators and drinkers.

This is the first of two articles discussing the colonization of tea. This article will focus on the history of colonization, and the next will address how colonization continues to impact the tea industry.

Table of Contents

Before We Begin

I believe that, as a white person, it’s important to talk about these histories, discuss the challenges they continue to create, and work to dismantle systems of oppression. I’ve done extensive research for this article, but most of these resources are based in white-supremacy, and I recognize that some of the facts, figures and stories here will be through that lens.

Furthermore, I will be making mistakes. In fact, you may even see mistakes in this article. My goal is to listen when mistakes are pointed out, apologies with humility and sincerity, and work to not make that mistake again.

Cultural Significance of Tea

To better understand the overwhelming impact of colonization, specifically with tea, I want to give a little cultural and historical background.

It’s said that in 2737 BCE, Emperor Shen Nong told his people to boil their water for safety. While he was boiling his own water, the wind blew some leaves into his pot. He was delighted by the elixir! Those were tea leaves!

Another version of that myth states, according to Tea Drunk, “during a long day spent roaming the forest searching for edible grains and herbs, the weary divine farmer Shen Nong accidentally poisoned himself 72 times. But before the poisons could end his life, a leaf drifted into his mouth. He chewed on it, and it revived him, and that is how we discovered tea.”

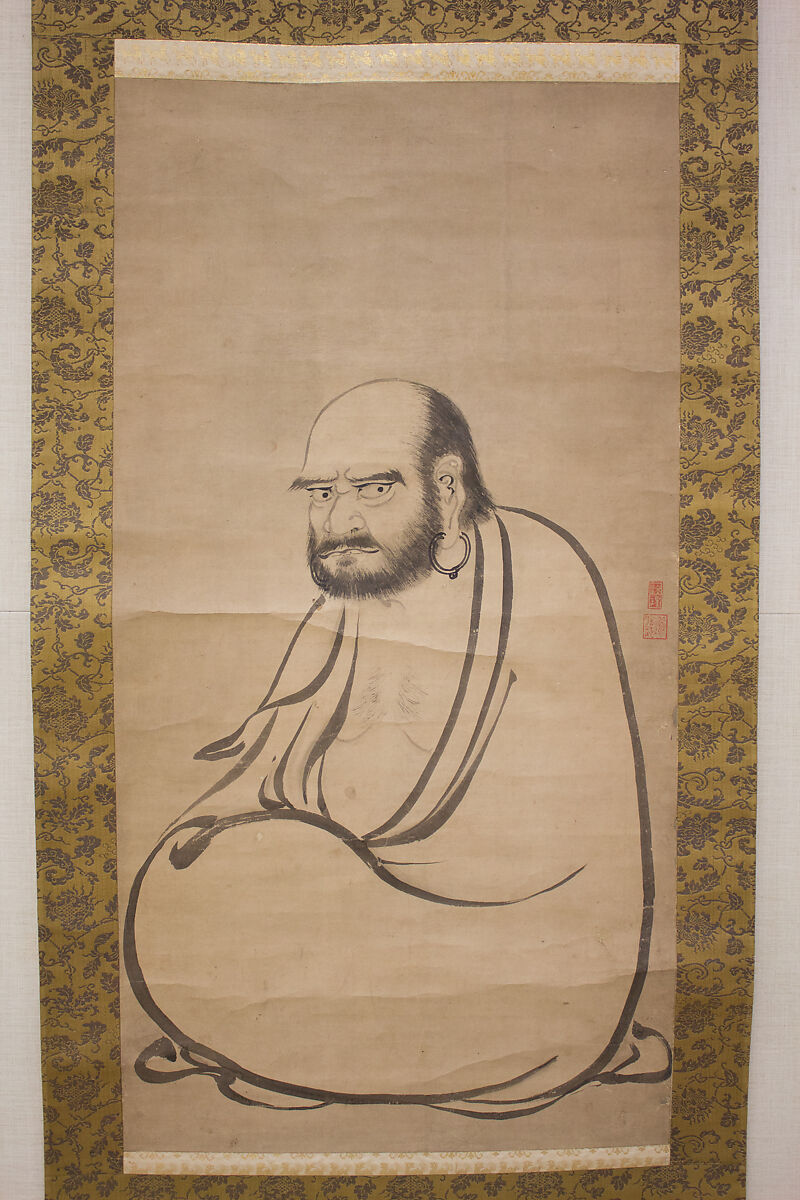

Yet another legend says that the monk Bodhidharma, an Indian Buddhist missionary in China, was frustrated that he fell asleep during meditation, so he cut off his eyelids, and where they fell on the ground, a tea plant sprung up.

The East India Company

Around the 1600s, tea was gaining popularity in Europe. The East India Company was a trading Goliath, moving goods to and from England at the time. One of these goods was tea. By the 1700s, the demand for tea in England was massive, and the East India Company had a monopoly on its trade.

During this time, the Chinese government had strict policies around tea trading with European countries. Traders were not allowed further than a day’s walk into the country from the ports. This insured the cultivation and production of tea was kept a closely guarded secret.

The word “monopoly” was also used to describe Chinese control of tea at the time. I believe there is a difference between controlling a market to maintain profit, and protecting a cultural staple to preserve the livelihood of a country’s population. We have to remember, tea was a luxury in England, and a pillar of society in China. So I don’t think the word “monopoly” applies to China’s strict regulations around tea trading the same way it applies to the East India Company’s iron-clad grip on tea trading in England.

In addition to regulations, China would only trade tea for silver. This was unfavorable for the British. In order to gain more access to tea, the East India Company, which at the time was partially under the control of the British Parliament, smuggled opium, mostly from India, into the country. This was illegal under Chinese rule, and had devastating effects. Widespread addiction to the drug crippled the Chinese society and economy.

This resulted in the first of two Opium Wars.

The Theft of Tea

Despite winning the first Opium War, through which the British gained access to 4 additional trading ports in China and very unfavorable trade agreements for China, the British still did not want to be subjected to China’s dominance in tea. In order to gain the control they wanted, the East India Company sent a Scottish botanist named Robert Fortune to the heart of China’s tea industry. Dressed in “mandarin garb,” Fortune stole tea plants, seeds, and production secrets, and brought them to company-controlled farms in India. This usurped the dominance of the Chinese tea trade, and changed the industry forever.

India, under colonial British rule from 1858 to 1947, remained the top tea-producing country until the 21st century, when China took the lead again.

Tea Slavery

Tea and slavery are inextricably linked in many ways. The tea trade moved in the same circles as the slave trade, along with the sugar trade. Because of the British obsession with tea, and their unaccustomed palates to its bitterness, sugar was a very important import. Sugar was grown, harvested and produced using enslaved people.

Modern slavery still exists today on tea plantations around the world. But that will be covered in the next article, because it is a topic too important to cover in one article.

Remembering the Past and Challenging the Present

Many white westerners – myself included – have taken immense pleasure in the celebration of tea. We’ve studied, sipped, tested, and tasted all types of tea. Some have led with cultural appreciation, some with cultural appropriation. For those of us whose culture is not one steeped in tea – it’s cultivation, it’s production, it’s importance – and for those of us whose ancestors were not slaves on farms reaping crops that made many others rich, we have to remember that tea is a sacred gift that we enjoy only because of centuries of colonization, warfare, torture, and indentured servitude.